- Home

- Heather Graham

Ondine Page 21

Ondine Read online

Page 21

He shifted again. She felt the covers being pulled warmly around her. And she felt his weight as he lay down beside her again.

And though she didn’t see him, she was certain that he had regained his original pose; that he was staring at the ceiling again, and that his eyes would be troubled with secrets and mystery; that his jaw would be hard, pensive …

Why?

She ached; she yearned to know. She longed to reach to him, yet she could not. She didn’t dare give more of a love than she could receive in turn.

She had her own grave problems to solve, she reminded herself sharply. She forced herself to call to mind the horrid things he had said to her—that she was nothing but a commoner, saved for his use. In time she must escape him—prove herself loyal, regain her birthright. He had taken much of her this night, but he had learned nothing of the king’s promise, nor would he.

None of these things could help her; none of them could hold her thoughts, her mind, or her heart. She was changed; he had changed her. She could never forget that her virginity had been shed upon this bed, with violence and tenderness, fury and laughter and—longing.

And she simply couldn’t stop thinking of Anne, thinking of her with a furious loathing. If the lady dared speak of Warwick’s endowments again, Ondine was quite certain she would tear her to shreds.

The lady Anne, it seemed, had the greater claim.

I am his wife! Ondine thought with anguish.

His gallows’ bride …

Taken by him at last, and never, never to be the same again.

Chapter 14

Sunlight was pouring into the room when she awoke, streams that danced from the panes upon her. Memory of the night past came upon her in a warm rush, and still dazed with sleep, she smiled, smug and pleased with that memory. Warwick! Ah, memory of his face, his touch, was all that came to her with that first light. Had he been beside her, she might well have sighed with the complacent pleasure of a kitten and cast herself awestruck against him.

But he was not beside her, and as she opened her eyes more fully, she saw him at last.

He stood by the window, completely dressed down to buckled shoes and plumed hat. His foot rested upon the rung of a chair, his thumbs locked into breeches, and he stared darkly and pensively out upon the brightness of the day.

Her heart first soared with the sight of him, then seemed to shatter like the surf against rocks as the grimness of his taut features worked into her mind.

She drew her covers up; she was uneasy, though she knew not why. Her smile slowly faded just as he turned to her.

“Warwick—”

He doffed his hat and bowed low, without mockery this morning, yet with something far worse: the greatest reserve, the most chilling distance.

“My lady, I do apologize for my most atrocious manners of last eve. 1 fear I drank too deeply, and too well, and matters here are tense at best. Do forgive me.”

She stared at him blankly, unbelievingly. Then she raised her own shield of ice to combat the fever of pain, and twisted with her covering so that her back was to him.

“Just do get out of here, please.”

He did not move; he hesitated. Then he came to her back, and she shivered as she felt the line his finger drew there.

“I didn’t know, er … I did not suspect …”

She swung around, staring at him. “Know what?”

He grated out some impatient sound, a barely articulate oath. “For God’s sake, girl, I married you off the gallows!”

“And … ?” she demanded warily, her temper instinctively growing as she sought his meaning.

“I did not expect to find a maid, untouched, but a woman of certain experience.”

“What? Oh!” She forgot that he was completely clad, that her covers were her only defense, and sat to throw her pillow hard against him. He caught it with a mere tightening of his mouth.

“My God, you’d come from Newgate—”

“Newgate! Ah, yes, my lord of Chatham! I came from Newgate. How dare you assume that all those wretches dragged to that horrid place are whores, since they be debtors or beggars—”

“Or liars, cutthroats, and thieves? Forgive what was stolen, Countess, by a drunken boor; had I known you were among the great virtuous masses of Newgate, I’d never have erred. And then, Countess, there was the matter of the king, you see. You swayed and laughed and teased with him like a mistress well versed in the arts.”

Retrieving her covers, Ondine lowered her head. “Get out!”

He bowed low to her once again, and she hated him for it and for the vibrant sarcasm in his words.

“As 1 said, my manners were atrocious. I shall endeavor, madam, to improve them in the future.”

He turned then and strode to the door, but paused there. “I’ve business with the king this day and the next, yet now that I am here, I’ve no wish to stay longer than I must. Be prepared to leave, for I intend to cut short our stay as much as possible.”

He opened the door and closed it behind himself. Ondine stared after him, still incredulous. Tears burned her eyes, and she dug her fingers into the sheets, fighting them. She would never, never understand him. Never in a thousand years …

She turned about, burying her head into the pillow as a sob tore from her. How could she have been so foolish as to forget? Forget that his reputation was a rage about court, that it seemed that one woman was but the same as another to him.

She pushed her face from the pillow at last. “Bastard! Bastard!” she hissed, miserably clenching her eyes together. She had allowed herself to care …

She rose, shivering as she rushed naked to the pitcher and bowl. She splashed water brutally against her face.

The king had suggested she leave him, and leave him she surely would. Newgate whore, indeed! She was a duchess in her own right, and, by God, she would prove it and he would eat the dust that flew from her heels.

She paused then, shivering once again. No. He had saved her life in a devil’s bargain she still did not understand. She was in his debt. She would pay that debt, for it was owed. But when it was paid in full, she would depart as swiftly as the wind.

Warwick spent the day in the king’s chambers, listening as advisors warned Charles about the fear of Papists, still riding high in England. The king’s face was set, for it was his brother, James, heir to the crown, whom they attacked.,

Charles despised intolerance; he had a leaning toward Catholicism himself—yet a penchant for his throne that kept him ever wary and prudent. As his maternal grandfather—the great Henry IV—had once claimed,“Paris for a Mass!” Charles would remain a Protestant king to remain a king.

“Leave off with this endless debate!” Charles said wearily. “We’ve graver matters at stake!”

And so the business of the kingdom turned to finance, another endless debate, for Charles was nearly always in need of funding.

Warwick lost touch with the voices around him. He sat at apparent attention; he was nothing but a marble presence. His thoughts—remorse, shame, hunger, and longing—consumed him, and he feared he would never escape the tangle of emotion. She haunted him more now that the scent and sight and sound and touch of her were real in his memory, so very real that he could see all of her, know the detail, the beauty …

He had all but attacked her. His wife. The wretched ragamuffin he had plucked from the streets—the woman he had sworn to protect, but never love. Protect! Dear God, from what? Had he gone insane? What had he expected to prove here? Hardgrave was in attendance, as well as the lady Anne. Yet how could Anne whisper to Ondine in the halls of Chatham Manor? How could Hardgrave?

Hardgrave was so near, a neighbor. There were hidden chambers and false doors within Chatham.

But the hounds would not accept a stranger in the hall, nor could Warwick imagine Hardgrave, with his bulk, scampering through the halls to whisper to his wife!

His head was pounding. He had wronged Ondine; wronged her gravely. She had been as

chaste as the snow, yet would be no more when he released her from this travesty into which he had summoned her.

Could he release her? He did not think that he could …

God rot it all! But he had never felt this passion so deep, it ruled all thought, dulling the mind and tricking the actions! This envy, this jealousy … this absolute sense of possession. It was a painful thing. It tore at the gut and the heart and the soul, and he wished fervently that he’d never seen her face, never felt her spell entrap him.

Think, man, it was time to watch and judge. Anne was as jealous as a spiteful little cat, pleading, cajoling, threatening. Hardgrave and Warwick were keeping their distance, like great wary bears. Hardgrave watched Ondine with hunger lacing his eyes, but what man did not? It had all been worthless. All that he had managed was a time of agony, seeing his wife the center of endless desire— his own! Taking her …

But he could not do so again. He was no rapist, no seducer of innocents. Nor did he dare love her, though love her he did. She didn’t know his bargain, but it had been sealed in his heart. She had been bait for a killer, and for that she was due his greatest debt, her life and her freedom.

Two more nights of misery.

No, there was endless misery. For at Chatham she would still be near.

But she would have her own chamber. He could not go to her again; it would not be fair.

Two more days. Days of watching her laugh and smile and charm everyone around her. Days of feeling the coldness of her gaze when it fell upon him. Days of watching Anne eye her in constant and dangerous speculation, while Hardgrave stared after her with lust and cunning in his eyes.

On a sudden thought Warwick made the announcement, the next day, of his coming heir at court. Charles and Catherine were thrilled.

Anne narrowed her cat’s eyes furiously.

Hardgrave appeared to plot all the more.

Ondine stared at him, as if her eyes were glittering steel swords and she would gladly use them to disembowel him.

But nothing happened, except that his temper grew shorter as he tried to sleep upon the settee, tried not to think that just beyond the door she breathed and slept, that beneath her nightdress she was warm and supple and curved for a man’s pleasure, that she was a woman of grace and passion that raged deeper than even he had imagined …

On the third day they left before the sun had risen. Warwick was atop the carriage with Jake; Ondine was alone inside of it.

They reached Chatham, and Warwick found his life ever more miserable. He could not leave her at night, for it was here that she had claimed the whisperer came to her, calling her.

And she was so cool, so aloof and polite, cordial, moving about with the rustle of her skirts, the scent of her perfume, her chin held high, her eyes sweet enigmas. She spoke as if they were acquaintances, and she kept her distance most serenely. She laughed and smiled and chatted—with Justin and Clinton. Mathilda came to adore her more and more.

Warwick grew more moody, more reserved, stiff and straight and cold as ice … ice that housed a fire. He could not break the spell, change the beguilement. Again, he felt something in him simmer, and it was dangerous, so dangerous …

From Justin, Ondine learned that Anne could be a jealous beauty, though she collected lovers herself as another woman might add gowns to her wardrobe. She had assumed—after Genevieve’s death and the demise of her husband—that she would marry Warwick, though Justin stated with laughter that Warwick, had he not been so strange with brooding sorrow and anger after his first wife’s death, would not have married Anne anyway.

They’d been back at Chatham a week. She walked with Justin toward the stables as they spoke. Ondine had no permission to ride, yet she enjoyed seeing the horses where they stood in the fields, or in their stalls. Jake, she knew, would not be far behind her, but not close enough to hear her words, and so she easily plagued Justin with questions that he didn’t seem to mind answering.

“You didn’t know my brother long before your marriage, did you?” Justin asked her, his bright eyes alive with laughter.

“No,” she admitted, but told him no more. With a winning smile she placed a hand upon his arm. “So you see, dear Brother, I need all your help to understand my lord of Chatham.”

That much was true; she longed to understand the man, to discover what role she played, and then leave!

“Ah, fair Sister, touch me not!” Justin implored, smiling his flattery. “My brother’s bride sets a tempest in my own soul, and I am not made of stone.”

“I believe that he is,” Ondine muttered, the words slipping from her without thought.

“Ah-ha!” Justin declared, laughing. “So—this court excursion brought disharmony betwixt you, because of Anne, no doubt.”

She had no desire to explain the details of the estrangement in her marriage that Justin so obviously sensed and viewed with amusement. She moved forward to pluck a wildflower from the heath, then turned back to her handsome brother-in-law.

“Tell me more about Anne.”

Justin laughed, taking her hand and swinging it at his side so that they could continue their walk.

“Anne is a cunning vixen, nothing more, nothing less. She has partnered the king, among others, and from that alone, I can assure you, my brother never thought of her as anything other than amusement alone. The ‘beasts’ of Chatham are just that at times, my lady—proud and possessive. Beasts play where they will, but when they choose a mate, they do so with the gravest care, and might well be prone to kill for that mate’s honor and virtue. Can you foresee such a life with the lady Anne?”

Ondine did not reply. Warwick had, after all, taken her from the gallows, and he had, so it seemed, assumed her to be of the loosest morality.

She grinned sweetly at Justin, enjoying the lightness and laughter in his eyes, the tender flattery of his tongue, when all she received elsewhere was the most distant, forced courtesy.

“Tell me, Justin, do you know so much of beasts since you are of their number yourself?”

“Me? A beast? Nay, lady, never! The second child receives not the title, nor the land—but neither must he go through life with the label either!” Justin laughed.

Ondine laughed along with him, yet suddenly she was uneasy. Justin could hold the same intrigue in his visage as Warwick at times, the same ultimate charm, the same flirtation with danger. Did he ever resent his brother for the accident of birth, that Warwick held the title and the income?

It seemed that a cloud came just then, precisely, to cover the sun, to riddle her with chills of doubt. Ah, it was the madness of this place! It was her husband—oh, the devil should indeed take for a beast!—forcing her to a tempest only to dash her upon the coldness of a barren shore! There was no rhyme or reason to it, yet like him, she watched all with a jaundiced eye and found that mistrust came like a wall between any friendship, any closeness.

“Ah! Speak of the ‘beast,’ fair sister! There he is yonder, where we walk, with Clinton and Dragon!”

Justin caught her hand and hurried her along. She was flushed when she reached the stable yard, and being so, she felt that Warwick’s golden gaze touched upon her suspiciously, and she could not forget that his temper could be sparked to a high blaze with jealousy.

Clinton, observing them all from a casual stance, greeted them cordially. Warwick said nothing, but he had little time, for Justin moved in to touch Dragon’s warm muzzle, demanding of his brother, “Have you seen the colt in the field, then, Brother? I do warrant that the son shall rival the father soon!”

Warwick laughed at his brother, seeming to forget Ondine for the moment. “What? You say, for the colt is yours, Justin! I’ll wager easily and well that it will take many a year for even his offspring to rival Dragon in strength and speed!”

“Nay! One more year, and we’ll see to that wager!”

“Aye!” Warwick declared.

“You’re about to ride?” Justin said. “Wait but a moment, and your wife and I

might accompany you.”

The laughter faded from Warwick’s face; again he stared at Ondine in that harsh way she had as yet to fathom. Yet she cared little now; her heart pulsed with the excitement of riding. Surely he could not deny her when he rode himself!

“Ondine may not ride. I’ve an appointment with a Flemish wool merchant and haven’t the time to wait for her to change clothing. Nor should she be so reckless with her health and our— child.”

“I beg you, milord!” she said very softly. “I swear, I can ride well in what I wear! My health is excellent. The exercise would do me and”—she paused, challenging him with her eyes—“the child a world of good.”

She heard his tsk of anger and knew with a fleeting pleasure that she had annoyed and embarrassed him, behaving like an abused spouse before his brother and cousin.

“Come, then!” he said irritably.

“It will take no time to saddle a suitable mount,” Clinton said pleasantly, and Ondine gazed at him quickly with wide grateful eyes, further annoying Warwick, yet she did not care in the least.

“I’ll tend to my own mount,” Justin told his brother, “and there will be no wait at all!”

Ondine did not gaze at Warwick; she sped behind Clinton, finding a bridle even as he selected the saddle for a small chestnut mare. She thanked Clinton warmly for his support, yet thought fleetingly that Clinton, too, had that manner about him! Indomitable; arrogant for all that he was, pleasant when he chose, kind when he chose. But he, too, was a Chatham, not the younger in birth, but of improper birth. Chathams! All possessive, too proud. And around them lurked a shroud of mystery. She should fear, but she didn’t know what it was she should fear, only that whispers plagued the manor, and Warwick kept his secrets to himself.

“Come, my lady, now or never!” Warwick called out harshly.

Clinton boosted her onto the mare; she was aware that his hands were powerful, like her husband’s.

Justin paused for a word with Clinton; Ondine started off with Warwick. They were but paces from the stable before he turned to her, eyeing her most callously.

Deadly Night

Deadly Night The Uninvited

The Uninvited Dust to Dust

Dust to Dust Heart of Evil

Heart of Evil A Perfect Obsession

A Perfect Obsession The Keepers

The Keepers Pale as Death

Pale as Death Phantom Evil

Phantom Evil Hallow Be the Haunt

Hallow Be the Haunt Night of the Wolves

Night of the Wolves The Night Is Forever

The Night Is Forever Golden Surrender

Golden Surrender Kiss of Darkness

Kiss of Darkness Beneath a Blood Red Moon

Beneath a Blood Red Moon A Dangerous Game

A Dangerous Game Ghost Shadow

Ghost Shadow Long, Lean, and Lethal

Long, Lean, and Lethal Fade to Black

Fade to Black The Rising

The Rising And One Wore Gray

And One Wore Gray Rebel

Rebel The Unseen

The Unseen The Night Is Watching

The Night Is Watching The Evil Inside

The Evil Inside The Unspoken

The Unspoken The Night Is Alive

The Night Is Alive The Unholy

The Unholy Nightwalker

Nightwalker Deadly Harvest

Deadly Harvest An Angel for Christmas

An Angel for Christmas A Pirate's Pleasure

A Pirate's Pleasure American Drifter

American Drifter Realm of Shadows

Realm of Shadows Blood on the Bayou

Blood on the Bayou Sacred Evil

Sacred Evil Dying to Have Her

Dying to Have Her The Cursed

The Cursed Captive

Captive Hurricane Bay

Hurricane Bay Drop Dead Gorgeous

Drop Dead Gorgeous Ghost Memories

Ghost Memories All Hallows Eve

All Hallows Eve Dying Breath

Dying Breath Deadly Fate

Deadly Fate The Dead Room

The Dead Room Lord of the Wolves

Lord of the Wolves Ghost Night

Ghost Night Ghost Walk

Ghost Walk The Forgotten

The Forgotten Unhallowed Ground

Unhallowed Ground One Wore Blue

One Wore Blue Dead By Dusk

Dead By Dusk Night of the Blackbird

Night of the Blackbird The Dead Play On

The Dead Play On Bride of the Night

Bride of the Night Wicked Deeds

Wicked Deeds The Forbidden

The Forbidden Triumph

Triumph Out of the Darkness

Out of the Darkness Love Not a Rebel

Love Not a Rebel The Last Noel

The Last Noel Tall, Dark, and Deadly

Tall, Dark, and Deadly The Death Dealer

The Death Dealer Dead on the Dance Floor

Dead on the Dance Floor Law and Disorder

Law and Disorder Dark Rites

Dark Rites New Year's Eve

New Year's Eve Hostage At Crystal Manor

Hostage At Crystal Manor And One Rode West

And One Rode West Home in Time for Christmas

Home in Time for Christmas Killing Kelly

Killing Kelly Blood Night

Blood Night Tangled Threat (Mills & Boon Heroes)

Tangled Threat (Mills & Boon Heroes) Darkest Journey

Darkest Journey Glory

Glory Deadly Touch

Deadly Touch An Unexpected Guest

An Unexpected Guest Night of the Vampires

Night of the Vampires Seize the Wind

Seize the Wind Ghost Moon

Ghost Moon The Vision

The Vision Dreaming Death

Dreaming Death Conspiracy to Murder

Conspiracy to Murder Horror-Ween (Krewe of Hunters)

Horror-Ween (Krewe of Hunters) The Summoning

The Summoning Waking the Dead

Waking the Dead Danger in Numbers

Danger in Numbers The Hidden

The Hidden Sweet Savage Eden

Sweet Savage Eden Tangled Threat ; Suspicious

Tangled Threat ; Suspicious Mother's Day, the Krewe, and a Really Big Dog

Mother's Day, the Krewe, and a Really Big Dog Picture Me Dead

Picture Me Dead The Killing Edge

The Killing Edge St. Patrick's Day

St. Patrick's Day Seeing Darkness

Seeing Darkness The Dead Heat of Summer: A Krewe of Hunters Novella

The Dead Heat of Summer: A Krewe of Hunters Novella Crimson Twilight

Crimson Twilight Haunted Destiny

Haunted Destiny Devil's Mistress

Devil's Mistress Banshee

Banshee The Unforgiven

The Unforgiven The Final Deception

The Final Deception A Horribly Haunted Halloween

A Horribly Haunted Halloween Haunted Be the Holidays

Haunted Be the Holidays Deadly Gift

Deadly Gift Easter, the Krewe and Another Large White Rabbit

Easter, the Krewe and Another Large White Rabbit Haunted

Haunted The Silenced

The Silenced Let the Dead Sleep

Let the Dead Sleep Christmas, the Krewe, and Kenneth

Christmas, the Krewe, and Kenneth Big Easy Evil

Big Easy Evil Sinister Intentions & Confiscated Conception

Sinister Intentions & Confiscated Conception Haunted Be the Holidays: A Krewe of Hunters Novella

Haunted Be the Holidays: A Krewe of Hunters Novella Blood Red

Blood Red A Perilous Eden

A Perilous Eden Slow Burn

Slow Burn Strangers In Paradise

Strangers In Paradise Bitter Reckoning

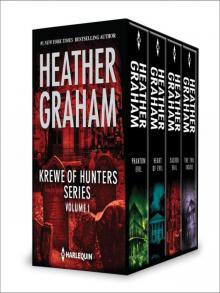

Bitter Reckoning Krewe of Hunters, Volume 1: Phantom Evil ; Heart of Evil ; Sacred Evil ; The Evil Inside

Krewe of Hunters, Volume 1: Phantom Evil ; Heart of Evil ; Sacred Evil ; The Evil Inside Do You Fear What I Fear?

Do You Fear What I Fear? The Face in the Window

The Face in the Window Krewe of Hunters, Volume 3: The Night Is WatchingThe Night Is AliveThe Night Is Forever

Krewe of Hunters, Volume 3: The Night Is WatchingThe Night Is AliveThe Night Is Forever Eyes of Fire

Eyes of Fire Apache Summer sb-3

Apache Summer sb-3 Sensuous Angel

Sensuous Angel In the Dark

In the Dark Knight Triumphant

Knight Triumphant Hours to Cherish

Hours to Cherish Tender Deception

Tender Deception Keeper of the Dawn tkl-4

Keeper of the Dawn tkl-4 Apache Summer

Apache Summer Between Roc and a Hard Place

Between Roc and a Hard Place Echoes of Evil

Echoes of Evil The Game of Love

The Game of Love Sacred Evil (Krewe of Hunters)

Sacred Evil (Krewe of Hunters) Bougainvillea

Bougainvillea Tender Taming

Tender Taming Keeper of the Night (The Keepers: L.A.)

Keeper of the Night (The Keepers: L.A.) Lonesome Rider and Wilde Imaginings

Lonesome Rider and Wilde Imaginings Lucia in Love

Lucia in Love The Gatekeeper

The Gatekeeper Liar's Moon

Liar's Moon Dark Rites--A Paranormal Romance Novel

Dark Rites--A Paranormal Romance Novel A Season for Love

A Season for Love Krewe of Hunters, Volume 6: Haunted Destiny ; Deadly Fate ; Darkest Journey

Krewe of Hunters, Volume 6: Haunted Destiny ; Deadly Fate ; Darkest Journey Keeper of the Dawn (The Keepers: L.A.)

Keeper of the Dawn (The Keepers: L.A.) Blood on the Bayou: A Cafferty & Quinn Novella

Blood on the Bayou: A Cafferty & Quinn Novella Double Entendre

Double Entendre A Perfect Obsession--A Novel of Romantic Suspense

A Perfect Obsession--A Novel of Romantic Suspense The Night Is Forever koh-11

The Night Is Forever koh-11 The Di Medici Bride

The Di Medici Bride When Irish Eyes Are Haunting: A Krewe of Hunters Novella

When Irish Eyes Are Haunting: A Krewe of Hunters Novella The Keepers: Christmas in Salem: Do You Fear What I Fear?The Fright Before ChristmasUnholy NightStalking in a Winter Wonderland (Harlequin Nocturne)

The Keepers: Christmas in Salem: Do You Fear What I Fear?The Fright Before ChristmasUnholy NightStalking in a Winter Wonderland (Harlequin Nocturne) Never Fear

Never Fear Dying Breath--A Heart-Stopping Novel of Paranormal Romantic Suspense

Dying Breath--A Heart-Stopping Novel of Paranormal Romantic Suspense If Looks Could Kill

If Looks Could Kill This Rough Magic

This Rough Magic Heather Graham's Christmas Treasures

Heather Graham's Christmas Treasures Hatfield and McCoy

Hatfield and McCoy The Trouble with Andrew

The Trouble with Andrew Never Fear - The Tarot: Do You Really Want To Know?

Never Fear - The Tarot: Do You Really Want To Know? Blue Heaven, Black Night

Blue Heaven, Black Night Forbidden Fire

Forbidden Fire Come the Morning

Come the Morning Dark Stranger sb-4

Dark Stranger sb-4 Lie Down in Roses

Lie Down in Roses Red Midnight

Red Midnight Krewe of Hunters Series, Volume 5

Krewe of Hunters Series, Volume 5 Night, Sea, And Stars

Night, Sea, And Stars Snowfire

Snowfire Quiet Walks the Tiger

Quiet Walks the Tiger Mistress of Magic

Mistress of Magic For All of Her Life

For All of Her Life Runaway

Runaway The Night Is Alive koh-10

The Night Is Alive koh-10 The Evil Inside (Krewe of Hunters)

The Evil Inside (Krewe of Hunters) All Hallows Eve: A Krewe of Hunters Novella (1001 Dark Nights)

All Hallows Eve: A Krewe of Hunters Novella (1001 Dark Nights) Tomorrow the Glory

Tomorrow the Glory Ondine

Ondine Angel of Mercy & Standoff at Mustang Ridge

Angel of Mercy & Standoff at Mustang Ridge Bride of the Tiger

Bride of the Tiger When Next We Love

When Next We Love Heather Graham Krewe of Hunters Series, Volume 4

Heather Graham Krewe of Hunters Series, Volume 4 A Season of Miracles

A Season of Miracles Realm of Shadows (Vampire Alliance)

Realm of Shadows (Vampire Alliance) When We Touch

When We Touch Serena's Magic

Serena's Magic Rides a Hero sb-2

Rides a Hero sb-2 All in the Family

All in the Family Handful of Dreams

Handful of Dreams A Stranger in the Hamptons

A Stranger in the Hamptons Krewe of Hunters, Volume 2: The Unseen ; The Unholy ; The Unspoken ; The Uninvited

Krewe of Hunters, Volume 2: The Unseen ; The Unholy ; The Unspoken ; The Uninvited Never Sleep With Strangers

Never Sleep With Strangers Eden's Spell

Eden's Spell A Magical Christmas

A Magical Christmas Forever My Love

Forever My Love King of the Castle

King of the Castle Night Moves (60th Anniversary)

Night Moves (60th Anniversary) The Island

The Island Borrowed Angel

Borrowed Angel Hallow Be the Haunt: A Krewe of Hunters Novella

Hallow Be the Haunt: A Krewe of Hunters Novella Why I Love New Orleans

Why I Love New Orleans The Last Cavalier

The Last Cavalier A Matter of Circumstance

A Matter of Circumstance Heather Graham's Haunted Treasures

Heather Graham's Haunted Treasures Tempestuous Eden

Tempestuous Eden Krewe 11 - The Night Is Forever

Krewe 11 - The Night Is Forever